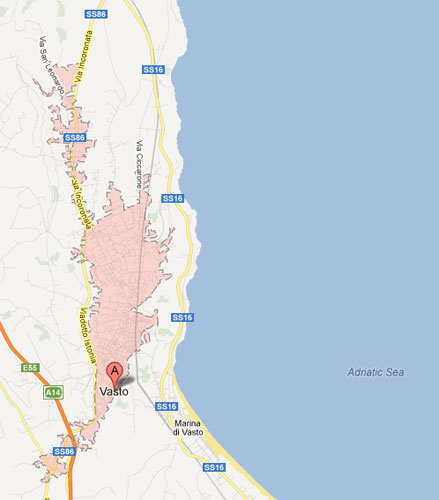

Vasto city to love is a delightful and tranquil small tourist town and seaside resort located in the south of Abruzzo, full of history, art, culture and lined with splendid beaches. There are more than 40 thousand people who live here and the population grows substantially in the summer with the arrival of tourists from Italy and all of Europe. The town of Vasto is bordered to the north by the river Sinello, to the south by the valley Buonanotte and the Adriatico sea to the east. The towns that are close by are Casalbordino, Pollutri, Monteodorisio, Cupello e San Salvo.

Thanks to the Apennines (Majella and Gran Sasso) only an hour away which protect the town from the cold winds and thanks to the sea which brings a cool breeze in the summer, Vasto enjoys a mild climate all year round.

Vasto city to love

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

State: Italy

Region: Abruzzo

Province: Chieti

City: Vasto

Coordinate: 42°6′41.72″N 14°42′29.5

Area total: 70,65 Km2

Population: 40.636

Density: 575,17/Km2

According to tradition, the town was founded by Diomedes, the Greek hero. The earliest archaeological relics date to 1300 BC, evidence of the first settlements. Histonium was one of the chief towns of the Frentani, situated on the coast of the Adriatic, about 9 km south of the promontory called Punta della Penna. The city is noticed by all the geographers among the towns of the Frentani, and we learn from the Liber Coloniarum that it received a colony, apparently under Julius Caesar. It did not, however, obtain the rank of a colonia, but continued to bear the title of a municipium, as we learn from inscriptions.

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

The same authorities prove that it must have been under the Roman Empire a flourishing and opulent municipal town; and this is further attested by existing remains, which include the vestiges of a theatre, baths, and other public edifices, besides numerous mosaics, statues, and columns of granite or marble. Hence there seems no doubt that it was at this period the chief city of the Frentani. (Romanelli, vol. iii. p. 32.) Among the numerous inscriptions which have been found there, one of the most curious records the fact of a youth named L. Valerius Pudens having at thirteen years of age borne away the prize of Latin poetry in the contests held at Rome in the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. The name of Histonium is still found in the Itineraries of the fourth century and it probably never ceased to exist on its present site, though ravaged successively by the Goths, the Lombards, the Franks, and the Arabs. Some local writers have referred to Histonium the strange passage of Strabo in which he speaks of a place called Ortonium (as the name stands in the manuscripts) as the resort of pirates of a very wild and uncivilised character. The passage is equally inapplicable to Histonium and to Ortona, both of which names naturally suggest themselves; and Kramer is disposed to reject it altogether as spurious.

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

Histonium has no natural port, but a mere roadstead; and it is not improbable that in the days of its prosperity it had a dependent port at the Punta della Penna, where there is good anchorage, and where Roman remains have also been found, which have been regarded, but probably erroneously, as those of Buca. The inscriptions published by a local antiquarian, as found on the same spot, are in all probability spurious. (See Mommsen, lnscr. Regn. Neap. p. 274, App. p. 30; who has collected and published all the genuine inscriptions found at Histonium.)

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus and proclaimed himself ruler of all Italy in 476AD, he in turn being replaced by Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths in 493AD. Following Theodoric’s death in 526AD, the Western half of the Empire became fully controlled by Germanic tribes until Justinian’s Byzantine re-conquest, which included the province of Samnium, of which Histonium was a key town. However soon after Justinian’s death the city fell to the Lombards becoming incorporated into the Duchy of Benevento and, later, succumbing to the Franks c774AD. Normans under Robert Guiscard in turn captured the Duchy of Benevento in 1053. Around 1076, Histonium was renamed Guastaymonis, or the Waste of Aimone (Italian: Il Guasto d’Aimone), following raids, hence its current name. From the thirteenth century it was part of the Kingdom of Naples, which later merged into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

In the 15th century the city’s urban structure was transformed by the condottiero Giacomo Caldora, who had become its lord. The Caldoras built new city walls still seen today: Torre Bassano in Piazza Rossetti, Torre Diomede in Vico Storto del Passero, Torre Diamante in Piazza Verdi and Porta Catena, with Castello Caldoresco as its primary defensive outpost.

In 1566 Turkish Ottoman naval forces, led by Piyale Pasha, destroyed much of the city by fire, including the Castello Caldoresco, the Church of Santa Margherita and the Palazzo d’Avalos (formerly a home of Vittoria Colonna – close confidante of Michelangelo – now the Musei di Palazzo d’Avalos).

Photo Michele Crisci

Photo Michele Crisci

Under the Spanish rule of southern Italy, Vasto became fief of the Marquises d’Avalos; in the reign of Cesare Michelangelo (marquis from 1697 to 1729), Vasto reached its zenith.

Only superficially shaken by revolutionary events in 1799 (a short-lived Republic of Vasto was immediately overthrown by the sanfedista, or loyalists), the city’s history was reflected in the nation’s throughout the Restoration to the Unity of Italy when a liberal elite governed. The poet and scholar Gabriele Pasquale Giuseppe Rossetti was born in Vasto on 28 February 1783. Rossetti’s published works include literary criticism, Romantic poetry such as his long poem Il veggente in solitudine of 1846, and his Autobiography. He is thought to be the basis of the character Professor Pesca, a political refugee from Italy and a member of ‘The Brotherhood’, an organisation placed contemporaneously with, and similarly featured as, the Carbonari, in Wilkie Collins’ 1860 novel The Woman in White. Gabriele went into political exile in 1821, settling in London, England. Gabriele died on 24 April 1854 and is buried in Highgate Cemetery with his wife Frances Polidori and daughter Christina Rossetti.

Photo Michele Crisci

In the age of Giovanni Giolitti, Vasto changed its architectural and urban features. The historical centre was redrawn and the foundations were set for drastic alterations during the 1920s and 1930s, with Mussolini decreeing a name change to Istonio in 1938, the official name until the liberation of the city in 1944.

Despite a devastating landslide (1956) that dragged a significant part of the eastern ridge – now Via Adriatica – into the gorge below, the years following World War II witnessed industrial, urban, parties and socio-cultural development. The city also discovered its tourist vocation: besides the progressive development of its beaches, Roman-era thermal baths, mosaics, cisterns and remains of an amphitheatre were found and restored.

Vasto city is the home of Harvard University’s Summer Program in Abruzzo, an intensive Italian language program for Harvard students.